Under the Byrne emigration scheme, and various other individual schemes existing at the time, approximately two thousand two hundred immigrants came to Natal from England during the period 1849 to 1852.1 John Clark was, of course, among them. By 1852, however, emigration from the British Isles to Natal had virtually come to an end. After 1857 emigration was resumed on a new basis.2Funds were then voted by the new legislative council of Natal to assist emigration of persons who were nominated for a passage by relatives or friends already in Natal. Over the period 1858 to 1864 nearly 1,500 immigrants reached Natal under this scheme.

Among those who took advantage of this new immigration scheme was the family of William Clark – later of Clark Road, Durban – which arrived in Durban on January 10, 1863. They were sponsored by William Clark of Durban, son of John Clark of York, Natal – and an as yet unidentified “W. Clark” of London. As we shall see, William’s family only managed to get to Natal on their second attempt. On the first attempt the family was shipwrecked off the Yorkshire coast. It was not until about eight months later that they left on what turned out to be the journey which eventually brought the family to Natal in 1863.

William Clark was born on July 6,1822. According to his gravestone in Durban’s West Street Cemetery he was born in Bradford, Yorkshire. But the 1861 Census reflects his birthplace as Osmotherley, Yorkshire, which seems more liklely to be correct given where his patents were apparently living at the time of his birth.

William was the fourth son of Leonard and Sarah Clark of Sutton Howgrave, Yorkshire. William married Jane Fenwick, who was born on March 21, 1823. The couple had six children, namely George, Ann Jane, William, Joseph, Robert and John Thomas (“Jack”).

William and Jane had been living in Osmotherley, on the outskirts of what is now the North York Moors National Park, when they made their first abortive attempt – in 1862 – to get to Natal. Prior to moving to Osmotherley the William Clark family had lived in Melmerby, near Ripon. It was in that village that George was born in 1847, Ann in 1852, and William in 1854. In 1855 the family moved to Osmotherley, where Joseph was born in 1857, and Robert in 1859.3 According to Ann Clark, her father “at that time was a wheelwright and joiner … [and] he and his family remained at Osmotherly for six years until he received a communication from his brother, Mr. John Clark, who … sent emigration papers… .” It is, therefore, the quaint and pretty village of Osmotherley which subsequent generations of Clarks should properly regard as their Yorkshire “roots”.

On the Clark family’s first attempt to get to Natal, they set sail from Middlesborough, Northern Yorkshire (on the River Tee). They sailed on a small coastal boat, the “Onward”, for London, from where they intended to sail to Natal on the vessel “Lady of the Lake”.4 The “Onward” was, however, wrecked within twenty-four hours of leaving port, at Flamborough Head off the Yorkshire coast. In an interview published in the Weekend Advertiser on April 16, 1932, William Clark Jr. (son of William and Jane) described the circumstances surrounding the sinking of the Onward as follows:

At 6 o’clock one morning in March 1861, the passengers of the vessel “Onward”, bound for London from Middlesborough, Yorkshire, were ordered on deck. Heavy seas had caused the cargo of railway metals to shift to one side, and the ship began to take in water at a dangerous list off Flamborough Head. On that ship were Mr. William Clark, now of 200 Manning Road, Durban, with his parents and two young brothers and an elder sister. As the boat was rapidly filling there was no time to get dressed and the passengers took to the boats as quickly as possible. Mr. Clark was six years old at the time, but he still vividly remembers seeing his father sitting on the tilted, high side deck of the ship holding on to the bulwarks with his younger brother (Joseph) pinned between his legs. Lashed to the deck nearby was a box on which young Clark and his sister were sitting; she had her arms clasped around his waist and their father had hold of his hands. The decks were continually awash with high seas and as Mrs. Clark, clasping her baby boy (Robert), made an effort to reach a lifeboat, a wave carried her to the side where she was saved by one of the crew from being washed overboard. She had had a presentiment that the boat would sink and had almost to be forced on board. The same wave had torn the box from its lashings, but before the next deluge the Clark family had managed to scramble on to one of the boats. Ten minutes later the Onward turned turtle and sank. The lifeboats were tossed about for two hours in the rough sea. It was raining, snowing and blowing and the passengers were without coats or caps. The Clarks were eventually picked up by a fishing smack and landed at Grimsby lighthouse. They had been without food for forty-eight hours. At Grimsby they each received a meat pie; and were then marched to an outfitter and clothed.

Although he was apparently a year out on the date, the accuracy of William’s account of the sinking of the “Onward” is corroborated by the following passage in “Shipwrecks of the Yorkshire Coast”5

A second screw steamer came to grief off Flamborough Head the following year, as a result of heavy seas. The Onward of Middlesborough left the Tees at 2.30 a.m. on 20 March 1862 with 17 passengers and a general cargo on her weekly voyage to London. A strong gale was blowing, the seas were heavy and showers of hail and snow made conditions even more unpleasant. At 8.30 p.m. the gale increased and a heavy sea struck the ship, knocking her onto her beam ends. The cargo broke adrift in the hold, the crew being ordered below to try and secure it. All canvas was taken in and the engine speed decreased. About 11.30 p.m. one of the bunker lids was carried away by the sea, and water poured into the engine room. The pumps would not function as they were choked up with small coals which had washed into the bilges, so the crew were ordered to bail. Shortly after midnight the fires were quenched and the engine stopped. The sails were re-set in an effort to keep the vessel moving towards land, and the bailing continued until 4 a.m. The water was gaining on them all the time, but efforts continued right to the last. Finally, at 5.30 a.m., the three boats were lowered and the passengers and crew abandoned ship. Ten minutes later the Onward went down, stem first, some fourteen miles east of Flamborough Head. At 8 a.m. the passengers and crew were picked up by the London schooner Petrel, which landed them, shivering and exhausted, at Grimsby.

The family lost all of their possessions when the Onward went down. After arriving at Grimsby they were given three days accommodation at an hotel, and train tickets to Bradford, where William found work. William Jr.’s account of the events following the sinking is as follows:

Mr. Clark, Senior, had their train fares paid by the shipping company to Bradford. All his possessions had been lost with the ship – he was going to have them insured on arrival in London before beginning the second stage of the voyage to Durban – and thus the family found themselves destitute. A parson friend of the family in Hosmotherley (sic Osmotherley) Yorkshire, heard of their plight and the parishioners subscribed for their relief. Mr. Clark journeyed there to receive the money: while he was away his family were without food, a situation which reduced Mrs. Clark to tears. Mr. Clark returned the next day and began work on the railway shops at 18 shillings a week, remaining there until October 1862.

After the experiences on the Onward, and the financial devastation which that event caused, it is surprising that the family did not abandon all thoughts of emigrating. However, after eight months at Bradford the William Clark family were again on their way to Natal. The second attempt to get to Natal was fortunately a little less eventful than the first, but it was still hardly the kind of experience that a modern traveller would consider acceptable. The family set out for London once again, in November 1862, but this time by train rather than coastal boat. At Gravesend they embarked for Natal on the three masted barque “Pharamond” – a 406 ton, 124 foot long vessel.

The Pharamond was built in Cardiff in 1855. The vessel was a barque of 406 tons, built of oak and pitch pine, and her dimensions were 124 x 26 x 17 feet. She was originally owned by Jolly & Co. of London, and her Master was Phillips. In the early part of 1862 the Pharamond was taken over by Hall & Co. and her Master was Searle. She was employed on the London to India route for most of her career, which ended in 1869.6Unfortunately, no photograph of the Pharamond has been found.

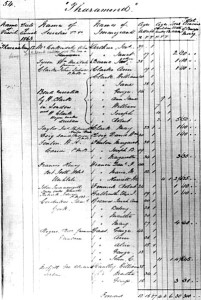

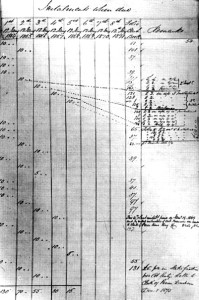

The official passenger list of the Pharamond in the Natal Archives reflects that the cost of the immigration to Natal of William and his family was underwritten by two sponsors, i.e. his nephew William – who is described as “Wagon Maker, Durban” – and the as yet unidentified “W Clark” in London. Records in the Natal Archives reflect that William duly paid off his indebtedness at the required rate of 10 pounds per year, by an initial payment in 1864, and a number of smaller payments of 4 pounds and 2 pounds respectively in following years. The ledger sheet reflecting those payments is reproduced below.

Jane Clark’s brother, Robert Fenwick, accompanied the Clarks on the Pharamond. He had also been a fellow passenger on the Onward, and is quoted as saying that “the night before the family boarded the Pharamond, [Jane Clark] had a vivid dream in which she saw the boat go down. But her husband would not listen to her foolish tears, and refused to change his plans”.7 William Clark Jr., in the interview referred to earlier, provided the following account of the voyage to Natal on the Pharamond:

Ocean travellers of those days did not know the taste of bread. Flour was distributed to the passengers, and Mrs. Clark used to make a large cake and pay the cook sixpence for baking it. Coming through the Bay of Biscay all the passengers were battened down for three days on account of the unusually rough seas which put out the fire in the cookhouse. Rounding the Cape a heavy gale was encountered, which blew down two of the masts. Jury masts were substituted and the Pharamond reached Durban in the first week of January 1863, after a voyage of seventy days from London.

The vessel was drawing sixteen feet of water, and as it could not enter port the passengers were transferred to small cargo boats and brought to the Point. It was a Sunday and there was no conveyance from the Point: the Clark family had to walk through the hot sand to the town, young William Clark fainting on the road”.8

The Natal Mercury of January 13, 1863 reported the arrival – on Saturday January 10 – of the Pharamond and its passengers, noting the Clarks under the category of “government immigrants”. The passengers on the Pharamond were classified under three categories, namely “cabin”, “steerage” and “government immigrants”. Because they apparently did not disembark until the Sunday, it seems that the Clarks were not amongst the passengers who were fortunate enough to make use of the recently opened Point rail service – as those passengers who disembarked on the Saturday were. One of the penalties, no doubt, of being the lowest class of passenger! According to a report in the same issue of the Natal Mercury:

The Pharamond all but anticipated the mail, and arrived simultaneously with it. She only left Derl two days earlier, and has made the first rate passage of 69 days from the downs. A list of 130 passengers by her appears in our shipping column. Many of them were landed immediately on the vessel’s arrival, on Saturday afternoon, and the scene at the Point represented the lively aspect usually presented on these occasions. A special train brought to town these new arrivals, to whom, as is our wont, we offer a hearty welcome, and the hope that this new year may prove specially happy to them in their new home. The rest have been brought ashore since.

That the new arrivals on the Pharamond were not universally happy with the reception which they received appears from a letter written to The Natal Mercury, which appeared on January 27,1863. It is written under the nom de plume “A Passenger on the Pharamond”, and appears under the heading “How government officials receive immigrants”. The letter reads:

Dear Sir – My addressing you at present is what I feel bound to do as a duty I owe, not only to my fellow passengers and myself, but to everyone interested in to the welfare and prosperity of this colony. I believe that there is a noble field here for the employment of English capital, but whether the inducements held out in England to all classes of immigrants to proceed to this colony are such as they find to be true and fully carried out after their arrival is a question that I am not at present prepared to enter upon. But it is almost superfluous to say that this colony requires a very large influx of labour and capital. Such being the case, most reasonable beings would naturally suppose that any immigrants who did come out would on their landing be welcomed by all especially by those who are indebted for their positions, and their bread, to the industry and hard uphill work of other immigrants, who have moulded the place into the position as a British colony it now occupies. It would seem however that to treat people here on their arrival with even common courtesy would be on the part of Her Majesty’s officials infra dig, but to bully, push them about and worry them is the dignified and respectable way for the officials and gentlemen to show their glorious authority. At the least British people would expect decency and civility on the part of colonial officials on their landing. Women and children are generally sea sick on the greater part of the voyage, and all passengers are more or less weary after a long sea voyage. Some are altogether strangers in a new country, without friends or relatives to greet them. Surely then a reception more calculated to quiet their anxieties and raise their spirits would be more conducive to the interests of the colony, more becoming the part of a civilized community, and not derogatory to the dignity of anyone. Then, again, I would draw public attention to the shameful way in which the luggage is tumbled about, and of course frequently damaged and destroyed; and also to the serious inconvenience arising to immigrants from its long detention in the hands of officials and others. This is a serious matter indeed to those who have only a few pounds in their pocket on their arrival, and which is the case with most. Their small means are nearly if not altogether spent by the time they are otherwise ready to leave for the country. The present is a time the emmigration from England to America, which a short time back was in its accustomed vigour, has now almost, if not altogether ceased, on account of the war in that country. Emmigration is consequently looking to other channels. We should therefore feel all deeply interested in seeing that this colony bears a good name, it being needless to say that the prosperity of each one individually is involved in it. I trust Sir that the subject of this letter will attract the notice of the inhabitants and that they will call on their representatives to take such steps as may ultimately lead to a discontinuance of the annoyance immigrants are at present subjected to on their arrival.

A PASSENGER ON THE “PHARAMOND”.

NB By immigrants I mean all classes of passengers.

The passengers on the Pharamond were apparently subjected to delays before the remainder of their belongings were landed, because the vessel was still outside Durban Bay, in the roadstead off the “Back Beach”, on February 10, 1863.9 The shipping columns of The Natal Mercury reflect that the Pharamond eventually sailed for Bombay on February 13, 1863. Presumably, therefore, it was able to cross the bar between the 10th and 13th of February, leaving immediately thereafter on its onward trip to India. The Mercury also reported, in its edition of January 16, 1863, that “the Pharamond’s passengers are, we hear, with very few exceptions, provided with occupation. This somewhat belies the impression so industriously circulated by some parties that Natal is a place to be avoided. The fact is, men of the right stamp have no fear of their future, if only they look ahead sufficiently.”

On their arrival the family stayed in the town of Durban for a year, and then moved to a wattle and daub house owned by the brother of the famous Dick King.10 William Clark Jr. states that the house had a sandy floor, which caused the chairs to sink into the soil in all angles!

On William’s arrival in Durban he started working for his nephew – and sponsor – William (son of John Clark of York).11 William (the nephew!) had established a wagon building business in Pine Terrace – now known as Pine Street. One of William Clark Senior’s fellow employees at the time was Samuel Crookes, who left the employ of William Clark (the nephew!) in 1865, to set up business at Renishaw on the South Coast. He subsequently turned his attention to sugar farming, and was the founder of Crookes Brothers Limited.12

William and Jane acquired title to a ten acre piece of land on the southwestern side of what is now Clark Road, and which extended from Brand Road to Bulwer Road. This lot incorporated all of the properties which adjoin the present York Avenue. In 1865 William built his house at the corner of Clark and Brand Roads, and he lived there until his death on May 26, 1903. The house was set well back from Clark Road, and actually faced Brand Road. This residence features in family photographs which have been preserved, including the family group and the photograph of William and Jane Clark which appear in this booklet. Subsequently William’s son Robert built his own residence on this same lot – but closer to the corner of Clark and Brand Roads. At the time of writing Robert’s original building still stands – right on the corner. It is now the offices of D. Smillie and Company.

William’s family set up a virtual “Clark Colony” along Clark Road. At one time or another William and his descendants owned all of the land to the south-west of Clark Road, between Clark Grove and Bulwer Road: George on Bulwer Road and along York Avenue; Joseph and Jack between Brand Road and Clark Grove; and Robert on the Brand Road corner. According to Russell’s “History of Old Durban” and Mclntyre’s “Origins of Durban Street Names”, both Clark Road and Clark Grove were amongst the roads above Umbilo Road which “were named after the original resident tenants”.13 However McIntyre wrongly states that the person after whom the road and grove were named was “George Clark”, who “came to Durban in 1849 under the Byrne immigration scheme”.14 The date and method of immigration may have been confused by McIntyre with the arrival of John Clark – who carne to Natal as a Byrne Settler on the vessel “Lady Bruce” – but in May 1850.15However, John Clark never lived anywhere near Clark Road. In any event, the area into which Clark Road falls was not opened up for occupation until 1856 or 1857,16 by which time John had left Durban for York, Natal. Moreover, John Clark’s obituary confirms that Clark Road was named after his brother William.17 There can, therefore, be no doubt that it is William Clark senior – and not his brother John, or anyone else – who was honoured by the naming of Clark Road and Clark Grove.

The Clark family was also involved in the naming of York Avenue. This lane – which formed part of William’s original ten acres – was established on land donated by “two sons” of William after he had acquired freehold title to the land.18” The identities of those two sons is uncertain, but one was undoubtedly George, who owned many of the properties on both sides of York Avenue. The other may have been William, who by 1890 had moved from the “Clark Colony” on Clark Road and built his home at 200 Manning Road.19

Victor Clark, who lived in his father Robert’s home adjoining that of William Clark senior, tells that as a young boy he used to incur his grandfather William’s wrath by pinching his fruit – apparently William maintained a tolerable orchard. Victor well remembered William senior as an old man who walked with a stick, because of a leg injury sustained in an accident at work, in which his knee was struck by an axe. Aside from having Clark Road named after him, the only other apparent memorial to William senior is the firm of Clark & Kent, of which he may have been one of the founders: a document in the Killie Campbell Museum (apparently submitted by May Eales, a grand-daughter), states that “he spent a number of years wagon and coach building in the firm of Clark & Kent”. We know that William junior was for a time a principal of that firm, and he may therefore have followed his father into the business.20

One cannot but admire the tenacity of William and Jane Clark, in persisting with their plans to emigrate to Natal, after the nearly tragic sinking of the “Onward”, and the consequent loss of all of their worldly goods. This is especially so when one considers that at the time of the sinking of the Onward the William Clark’s youngest child, Robert, was only two years old. It seems that William and Jane were made of pretty stern stuff – but for which characteristic many Clarks in Durban and elsewhere might to this day still be living in the picturesque villages of Northern Yorkshire!

1 Alan F. Hattersley, The Natalians, at p. 61 (Shuter & Shooter 1940)

2 Alan F. Hattersley, The British Settlement of Natal, at p. 222-3 (Cambridge University Press 1950)

3 The Natal Mercury, Saturday May 28, 1932: article on Ann Jane Wade (nee Clark) entitled "EarlyRomance and Adventure - Old Colonist's 80th Birthday".

4 The Natal Mercury, Saturday, May28, 1932, supra; Week-End Advertiser, Saturday, April 16,1932; Article on William Clark entitled "It Took Seventy Days From England To Durban".

5 Godfrey A. and Lassey P.J, Shipwrecks of the Yorkshire Coast, at p. 81 (Dalesman Books, 1976).

6 Extract from a letter to Stuart Clark, dated October 12, 1983, from the National Maritime Museum,London.

7 Unidentified newspaper cutting (probably The Natal Mercury) dated Tuesday, July 7, 1931, concerning Robert Fenwick, entitled "Old Natal Colonist Turns 94".

8 See also Joseph Clark's account of the arrival in Durban, in Chapter 6, and the news report of Robert Fenwick's death in the Natal Mercury of October 7, 1931.

9 The Natal Mercury, February 10, 1863.

10 Week End Advertiser, supra. It was Dick King, of course, who rode from Durban to Grahamstown in 1842 to seek relief when the Voortrekkers under Commandant General Pretorius beseiged Captain T. C. Smith's British force at Congella. See, e.g. Eric Goetzsche, Father of a City, the biography of George Christopher Cato, chapter 2.

11 Week End Advertiser, supra.

12 Robert F. Osborn, Valiant Harvest: The Founding of the South African Sugar Industry 1848 - 1926, p.319 (South African Sugar Association,1964); Hocking Renishaw: The Story of the Crookes Brothers pp. 50 -51 and 51 – 59 (Hollards 1992).

13 George Russell, History of Old Durban, p 333 (T. W. Griggs & Co. (Pty.) Ltd., 1971 - New Edition); John McIntyre, Origin of Durban Street Names, at p. 3113.

14 An interesting question raised by McIntyre's claim that Clark Road was named after "George" Clark is whether William Clark senior was perhaps also known as "George". Earlier versions of the writer's draft family tree reflected, for reasons which the writer has been unable to recollect, that the correct name of William senior was "William George". That tree had its origins in discussions with family members going back to the 1960's. There seems to be little doubt, however, that the name "George" was never formally part of William's name. Those of his grandchildren of whom enquiries were made in the 1980's are not sure of the true position, but do not discount the possibility that William may have also been known as George. However, it also seems possible that Mclntyre's sources merely confused William with his oldest son George, even though George was not yet twenty years old when Clark Road was named, and was two years old at the time of "George" Clark's supposed emigration in 1849!

15 See Chapter 9.

16 George Russell, History of Old Durban. supra, p 333.

17 See Chapter 9.

18 Note found at Killie Campbell Museum entitled "William Clark" believed to have been submitted byMay Eales, nee Clark, his grand-daughter (daughter of George).

19 Based on the date of an old photograph in the possession of Gwen Sanders, his grand-daughter.

20 See Chapter 5.